This October I made a game in PICO-8 for a month-long game jam. As an experienced non-game developer of over 20 years, I thought I’d write down my thoughts on the pros and cons of PICO-8, along with a quick walkthrough of the design of my game’s puzzles and code. Plus how it’s easy to be over-ambitious in a month-long jam!

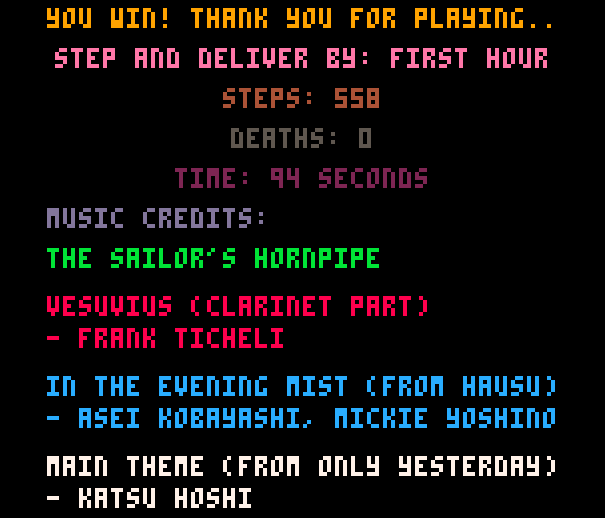

On October 27th I released Step and Deliver on itch.io, it’s a puzzle game with some basic roots in Sokoban, but the catch is you have a limited number of steps before you’re zapped back to your starting location. I’m reasonably happy with how it turned out, I think the step feature worked to create some interesting puzzles but also generally railroaded each stage with the limited actions available.

Let’s step into it all.

The game has a long provenance in my head, but in the end turned out to be a mix of Sokoban block pushing, a Death Stranding-like focus on mail delivery and planning a basic route, and even Blue Prince for a nod to its steps and refreshing fruit. The game is viewed from the top-down and features 16 single-screen stages with an envelope and mailbox placed on each level. The goal is to grab the envelope and drop it in the mailbox before you run out of steps; if you hit zero the game rewinds you and all other objects on screen one step at a time to its origin.

Movement is simple, a single step is limited to the four cardinal directions. You begin the game with five steps, grabbing an envelope or other objects refills them, and once dropped off in the mailbox allows you to run around freely in that stage, or even backtrack to previous. The game is built into four biome worlds with four stages in each, with different gameplay mechanics introduced in each.

I created all the art in the game, and the music are chip-tune versions of some songs I enjoy that I converted from sheet music into PICO-8 format. Honestly creating the music was one of the most enjoyable aspects of development, but I’ll get into that in a moment. Here are the music credits:

Absolutely no generative AI was used to develop the game, not in the sprite art or the code itself.

Built and designed as a fantasy retro console, PICO-8 was constructed with hard limitations in mind: a 16-color palette, limited number of sprites, map size, code character count, and even computations per frame. These limits exist intentionally not only to clamp down on scope, but to also spark creativity.

I first learned about PICO-8 like many others back in 2018 when I stumbled across Celeste Classic inside the game Celeste. It feels rudimentary when juxtaposed directly against the full Celeste experience, but it features all the same nouns and verbs as the full game: Madeline, jump, dash, spikes, strawberries, instant respawn, and more.

For the Triple Click Discord 2025 Game Jam, I didn’t have any illusions that I was a single major iteration away from making one of the greatest games of all time, but I did have a lot of fun learning and working with and against PICO-8.

For making a game with the size and scope of Step and Deliver, PICO-8 was basically perfect. I don’t have any skill with pixel art, but when a single sprite is 8x8 pixels large, it’s easy to sketch something out and call it okay. There’s no concerns with shading or dithering, and making a banana the same size as a boulder is no big deal. I updated the main character sprite once (though the trans rights colors were there from the start), and I never even bothered with animating it beyond flipping the sprite depending on the left/right direction you’re facing.

Along with a sprite sheet, PICO-8 offers a map editor to build out levels visually. I found this to be an incredible boon as it allowed me to lay out levels and even build in all the enemies, mailboxes, envelopes, and items right there on the map. I created special sprites for map objects and during game initialization converted all the map sprites to their in-game sprite along with creating their corresponding objects in code. Yes, I used object-oriented programming in PICO-8 to great success.

The sound effect and music editors are initially a bit baffling, I just drag my mouse on this sfx timeline to create a sound? Yep, that’s pretty much it. Want to make a jump sound, make the sound effect pitch go up, the opposite for falling down a hole. You can also create music by typing in actual notes, like I did when converting from sheet music. There’s a fun variety of instruments and effects to choose from, though most aren’t appropriate for music. As I said earlier, I had a blast making the chip-tune music, trying to make a familiar piece sound good in PICO-8 while also making it relevant to the game itself brought me a lot of enjoyment and helped make the game feel whole at the end.

While sprite and sound editing feels natural in PICO-8, coding is a different story. The built-in font is uppercase only and the editor is only 32 characters wide. I lasted about an hour dealing with this before downloading Visual Studio Code and installing the PICO-8 Lua plugin. From here on out it was relatively smooth sailing, with support for multiple files I could break up my program how I wanted into this structure:

The entire project can be found on my Github.

The biggest issue I have with PICO-8 tutorials is there’s a constant concern with limiting token count. A single PICO-8 game supports 8,192 tokens in its code, where every part of a line of code counts as a token. Step and Deliver used 6,835 tokens, plenty of headroom in the end. But throughout development I was concerned I would hit the limit. Tutorials constantly harp on token reduction count, which I think is probably only useful for a small minority of games. It just feels like an unnecessary distraction when trying to learn a new engine and framework. I don’t have a problem with the token count itself, as I think it’s great at limiting scope.

Tutorials will also feature very short variable names, making some things nigh unreadable. This is definitely a side effect of the PICO-8 code editor only being 32 characters wide, but I discarded this idea quickly once switching to VS Code. There’s a lot of value in readable, self documenting code with verbose variable and function names.

Definitely a double-edged sword to participate in a month-long game jam. On the positive side, it gave me some runway to learn PICO-8 and develop a game while dealing with my normal adult life as a parent of two high schoolers. On the other hand, my initial ambitions were far too lofty. My original plan was to make this a strand game and call it Strand and Deliver!

Throughout development I kept trying to figure out how to integrate strand elements, allowing players to influence each other’s games in different ways, such as sharing items. I hadn’t figured it out all the way through the game, even while investigating how to use PICO-8’s GPIO functionality to talk to Javascript outside the game. I realized on the 27th that it might take me an entire additional week to get the strand stuff to work and that it would mostly be coding I didn’t find interesting. Let alone the fact I didn’t have a gameplay hook! It was a simple decision to drop the idea and rename the game.

All in all, I’m happy with how Step and Deliver turned out, give it a try and try and beat my high score!