In 2024 I completed my multi-year journey of playing every single NES game released in North America. I booted up 766 games in total, beating 141 of them. As I gathered my thoughts on the huge library I had just waded through, two impressions rose to the forefront:

The inaugural First Hour Seal of Quality goes to Summer Carnival ‘92: Recca, the best shmup on the NES, exclusive to Japan for 20 years.

Released in 1992 when the Super Nintendo had already been out a full year, Recca didn't light the sales charts on fire as its “raging fire” kanji would indicate. Left to languish on a usurped platform, Recca’s legacy would require time to develop, but it had the right factors to be impressive even 30 years later.

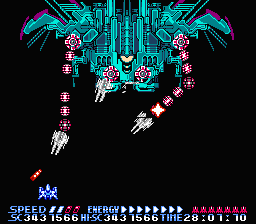

When I first played it I was absolutely floored by its locked 60 fps frame rate with dozens of ships flying across the screen. Too many shmups on the console play like Gradius or 1942, sluggishly tossing enemies at you as sprites flicker and the game slows down. Recca feels like a miracle.

I shouldn't be too hard on Gradius, Recca was released seven years after it, when developers had mastered the NES. Lead developer Shinobu Yagawa basically invented the bullet hell subgenre with his Summer Carnival release. Eschewing expected staples such as individual stages or moments of downtime for instead 25 minutes of chaotic, constant action. It's the kind of game where if you're not shooting, you're automatically charging a bomb instead.

Recca features two sets of power-ups that can be selected and upgraded individually: a primary and secondary fire. You can mix and match to get a spread shot along with a rotating missile, or a homing gun combined with backwards cannons. There's five options for each and can be enhanced by collecting additional drops.

You can also control how fast your ship moves by pressing the Select button to cycle through four speeds. Slower, more precise movement is very important when the screen is full of lasers. And if you're into high scores, your tally rapidly increases when you're not firing your weapons, making for some interesting strategies on how best to take out a squad of enemies in Score Attack mode.

What allows Recca to rise above the rest simply boils down to its ultra smooth gameplay, well designed enemy patterns, and numerous giant bosses. Deaths feel fair even while the game is very difficult. It’s relatively short so working on the patterns isn’t out of the question, just be prepared to grind if you don’t want to use save states or cheats.

In retrospect there feels like zero reason Recca couldn’t have been released outside of Japan. The menus are in English already and the credits, opening with “SUPER HARD SHOOTING GAME - RECCA,” are also completely presentable. Maybe Nintendo passed because of its difficulty? It seems unlikely it was because it was too late in the console’s cycle, a full 141 games released after June 1992 including Kirby’s Adventure, Dragon Quest IV, and finally Wario’s Woods in December 1994.

Or maybe Recca was just doomed to disappear. Groundbreaking games are often rediscovered years or decades later as fans and historians trace genre and design lineages. The game was also locked to the NES, never seeing an arcade release where most shmups at the time originated. Lead developer Shinobu Yagawa would later go on to create bullet hell classics such as Battle Garegga, Ibara, and Muchi Muchi Pork.

In honor of Recca being the first recipient of my First Hour Seal of Quality and topping my list of great NES shmups, I’d like to call some others out:

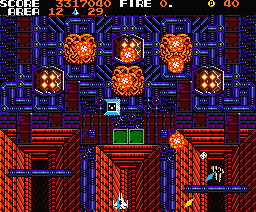

Siblings Asuka and Maya tackle a monster invasion in an impressive looking shooter complete with terrain destruction, ship transformations, and smooth diagonal scrolling. It definitely suffers from more technical issues than Recca, but the slowdown doesn’t feel too bad with its beautifully animated backgrounds and fun ship design.

On the surface it seems pretty typical of a shmup at the time, but this vertical shooter has some unique artificial intelligence that considers your current ship loadout, how often you die, your ability to take down bosses within a certain time limit, and more to adjust the number of and how aggressive the enemies are on the fly. It’s also a very long game, with 12 levels that take about an hour to play from start to finish.

Gotta love a game where the opening cutscene features a giant bunny rabbit ravaging a city. Gun Nac embraces the weird: craters on the moon can be blown up to reveal moon man faces, the between level shopkeeper has a hoard of missiles and bombs behind her, and of course, deadly hares roam every stage.

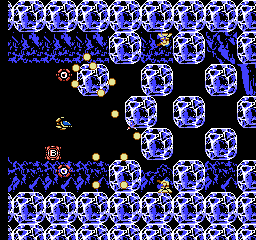

Finally, a horizontal shmup makes my list, this game is a blast to play and features a colorful palette. Its standout stage is an ice level where you have to shoot giant blocks of ice to move them around so that you can maneuver the auto-scroller in time and avoid being disintegrated on the left-hand side of the screen. I love seeing this kind of ingenuity.

The craziest game on the NES, bar none, is Zombie Nation. You play as the floating severed head of a samurai, sent to the United States to defend against an alien zombie attack. Buildings are destructible ala Rampage, but this time from your fiery breath. Zombie Nation is the game where you do one hundred times more damage in defense than the bad guys. I love it.

I’ll leave you with Shinobu Yagawa weighing in on the game difficult discourse back in 2010:

Interviewer: Do you think there is a trend in making games easier, not only in the shooting genre?

Shinobu Yagawa: I don’t really pay much attention to that… though maybe that’s why people say my games are difficult. (laughs) In the past it was normal to play and the memorize parts, or to watch someone else play and memorize what they did. Well, even back then, there was definitely a trend with making games easier, though I didn’t want them to. (laughs) I think its natural that players should actively work at things themselves.

To say it somewhat negatively, I make games for myself, and if I think its good then its fine, and this goes for difficulty settings as well. So I don’t give much concern to what fans will think. It isn’t that I don’t hear others opinions, but that I listen to and reflect on them, but to what degree I incorporate their ideas is up to me.